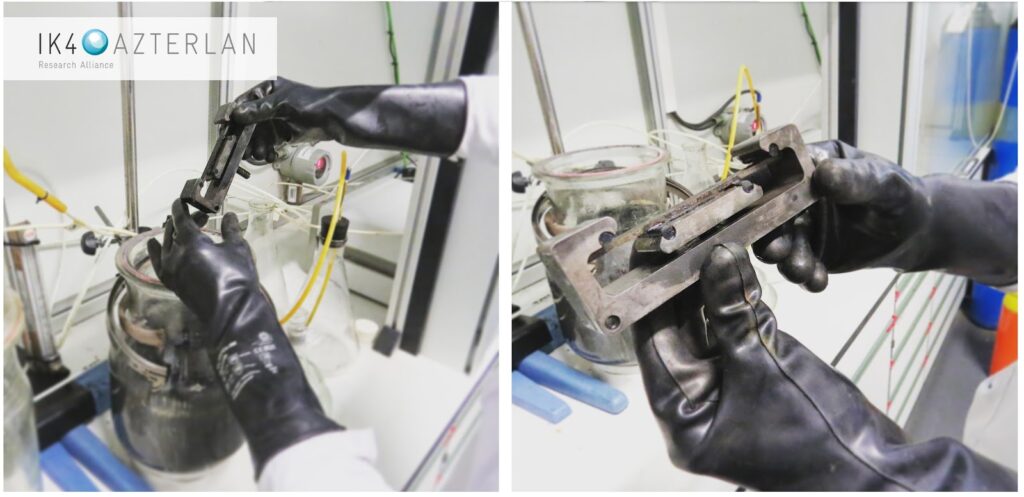

Hydrogen induced corrosion test at IK4-Azterlan metalic materials’ characterzation labs

Anyone who is fan of Agatha Christie’s novels or detective series will know that the real ability of the forensic analyst or investigator is not to determine the cause of the death of the victim, but discover the guilty of the murder. You will not be a reputed criminologist if during the examination of a body you just say that the victim has died because someone has stabbed him on the chest. On the contrary, the work of a good researcher goes through the analysis of the knife in search of traces, gathering of information on the identity of the victim, and examine thoroughly the crime scene to collect any evidence that may help to clarify the misdeed.

Corrosion may appear on many metals and alloys, and in very different ways. Since the general tendency of metals is to get a thermodynamic state with lower internal energy, corrosion is a natural and spontaneous process, which depends on factors such as the temperature, the medium or fluid in contact with the metal, and the nature itself of the latter. Corrosion is an inevitable process, but sometimes premature failures occur. And when a metallic part “dies” due to this phenomenon, it is necessary to initiate an investigation to clarify the cause and origin of the incident.

The victim: the metal corroded

Every forensic investigation starts with the autopsy of the body. The characterization of the material that has suffered the failure is essential to determine if its properties met the requirements of the applicable standards or specifications, or on the contrary, if there is a metallurgical irregularity conditioning the failure.

As a firearm leaves particular fingerprints on the projectile, which can be traced to determine the identity or type of weapon used, corrosion also leaves its mark on the material. Generalized, intergranular, pitting, on induced by tensions, all possible forms of corrosion show certain morphological features that allow the identification of failure mode by visual inspection, or with the aid of microscopic analysis.

“Generalized, intergranular, pitting, on induced by tensions, all possible forms of corrosion show certain morphological features that allow the identification of failure mode by visual inspection, or with the aid of microscopic analysis.”

The suspect: the corrosive agent

Just the effect of air and humidity on a metal part can cause oxidation, but in industrial environments is more common for the corrosion to be related with the presence of some pollutant or aggressive elements that accelerate this process. Although there are other elements that can also cause accelerated damage, such as sulfur, when a part undergoes premature corrosion, allmost in all cases of times the same suspect appears: chlorine.

Belonging to the halogen group, with the highest electronic affinity and the third mayor electronegativity of the periodic table, and due to its great capacity to steal electrons (that is, to oxidize) from other elements, is the most common “murderer” of steel and other metals and alloys.

The crime scene: environmental and service conditions

Having all the information related to the service conditions of a failed part is vital. In many cases, detecting the presence of chlorine in the corrosion byproducts is not enough to clarify the failure root cause. The knowledge of the service conditions is essential to trace and to locate the origin of this element, although, in most cases, the lack of knowledge of the client leads to the formulation of the typical question: “where does chlorine come from?”, whose answer is not as simple as it seems to be.

On the contrary to what one might think, chlorine is not an exclusive element of seawater and coastal areas. It is essential for many life forms and intervenes in numerous biological processes, and its abundance within the earth crust is greater than that of common alloying elements of stainless steel such as chromium and nickel. You can find it in chemical products of industrial and domestic use, in the form of dissolved salts or in solid state, such as in rocks or minerals. And all these chemical forms of chlorine can cause corrosion phenomena on metals if the adequate service conditions are met.

The crime partners: residual stresses and hydrogen

Sometimes chlorine does not act alone. In stress corrosion processes it needs a tensile component, and without it, is not capable to cause damage. A typical example is the stress corrosion cracking of austenitic stainless steels. Other times, chlorine is not the main responsible of the damage, but the hydrogen released as a corrosion byproduct, usually due to a galvanic reaction. In these cases, the failure is not produced by a mechanism of corrosion itself, but by a mechanical failure. That is the case of the so feared hydrogen embrittlement of high strength steels, known as Hydrogen Induced Cracking (HIC) or Environmentally Assisted Cracking (EAC).

Although chlorine appears in these mechanisms, we must not forget other phenomena of corrosive nature and caustic origin, which can also affect other types of metals, such as the season cracking of brasses, or the hydride formation in titanium alloys, for example.

Case closed: determination of corrosion failure

Not everything is as nice as we see on TV. While Horatio Caine and his team solve crimes in a single day, determining the ultimate cause that has produced a corrosion failure is sometimes a task not free from difficulty, which can take weeks.

The general tendency is to blame the metalic material, but in the vast majority of cases are the service conditions that produce the failure of the component, due to an inadequate maintenance, a design failure, o an improper material selection.

The evidence obtained in the

analyses of metallurgical characterization are a great help, but they are not enough to give a verdict. It is the experience of

IK4-Azterlan Metallurgy Research Center technicians in the interpretation of the results, and especially in the knowledge of metals and their behavior against corrosion which is decisive for the resolution of the case. Thus, with the proper knowledge and the adequate information, it can be said that “the perfect crime” does not exist in corrosion.